Parents feel a heavy burden to protect their kids from online harm. Threats such as cyber-bullying, predators, and unwanted content are real, and it’s understandable to want to put tight restrictions in place. But what if the very tools we use to protect our children are creating unintended consequences? Over-monitoring can undermine trust, limit children’s development of independence and online resilience, and even expose privacy vulnerabilities. Here’s what the research shows and how parents can find the perfect balance.

Where did we go wrong?

66% of parents surveyed say that parenting is harder today than 20 years ago, and digital technology is to blame.[1] Parents monitor in a variety of ways, including limiting screen time, checking websites, requiring password access, using GPS tracking, and checking social media following/friending.[1] Yes, tighter supervision sounds like a necessary solution in a world full of endless apps, social networks, and online risks, but is it?

A study conducted by the University of Central Florida found that parental-control apps, which allow for deep monitoring of children’s online activities, were associated with more, not fewer, online risks for teens. More specifically, the study found that teens whose parents used these apps reported unwanted explicit content, online harassment, and sexual solicitations. This doesn’t mean monitoring caused the risks; instead, parents often turn to these apps because their teens are already encountering online issues. The researchers concluded that instead of building digital competence and trust, many of these apps fostered a control-heavy and distrusting family environment.[2] So, instead of turning to these apps for help, try Dr. Bennett’s Connected Family Course.

Another study of children’s apps found that even “family-friendly” apps often include trackers, location permissions, or mislabeling of age ratings.[4] Further, children and teens with over-monitoring parents saw their parents as intrusive and were more likely to hide, deceive, and intentionally misbehave.[4] All in all, when monitoring feels oppressive, kids may respond by hiding and lying rather than being open and honest.

What does that mean for parents?

What does that mean for parents?

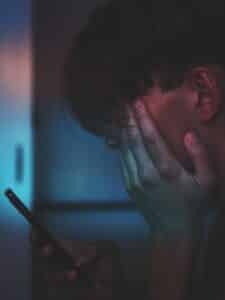

If the goal is safety, forced online surveillance may undermine the trust between parent and child and may hinder the open and honest communication we should be working to establish. As we teach in our Screen Safety Essentials Course for families, just implementing controls isn’t enough. One of the most damaging costs of over-monitoring is to trust and self-regulation. When children know they are constantly being watched, they may feel that their parents don’t believe they are capable of making responsible choices. That can lead to secrecy, feelings of giving up on communicating openly, and a lack of connection or engagement with parents.

“Why tell mom and dad if they won’t believe me anyway?”

I found myself asking this exact question at 12 years old when I made my first Facebook account and kept it a secret. I didn’t want to get in trouble, and I wanted to connect with my friends outside of school. I felt left out. But, when I asked my mom if I could open my own account, she said no. When I asked her why, she had no answer. So, I took it upon myself to create an account anyway.

I lied about my age so that I could create the account without parental supervision, and I kept it a secret. I would use it when she was not paying attention. My intentions were pure, and I did use it to connect with friends. But, of course, like with all online platforms, creepy older men would try to befriend me or message me.

GetKidsInternetSafe’s mission is to improve parent-child relationships AND screen safety. Had my mom and I had access to the GKIS Social Media Readiness Course, we would have been able to find a safer middle ground for me to connect to my friends. Not only would I have learned more about screen safety and been better equipped to solve online problems independently, but my parents and I would have engaged in healthier conversations and maybe even gotten closer. Ultimately, I would have been prepared to protect myself from getting into a relationship with a 17-year-old. Read The Hidden Dangers of Online Grooming: I Was Only 13, to find out how my lack of preparation for having social media resulted in me forming a premature physical relationship with a young man who was four years older than me at that time.

How Can We Do Better?

One of the most effective ways to guide children safely online isn’t through hidden surveillance, but through connection, conversation, and shared agreements. When parents begin by listening to their children about what worries them, what they enjoy, and what feels out of control, they build a foundation of trust. That trust becomes the launch pad for screen-time guidelines, digital boundaries, and the kind of autonomy children need to develop resilience. GKIS emphasizes this approach through its Connected Family Screen Agreement, a free tool designed to invite open dialogue instead of enforcing silence. It helps kids understand why parents have concerns and utilize safety tools and techniques.

Instead of solely relying on rigid controls, the path to healthier online habits includes tools, skill-building, and gradual transition. GKIS’s Screen Safety Toolkit isn’t a spy-kit; it’s a resource for families to use as practical checklists, conversational prompts, and strategies to empower children rather than just restricting them.

By investing in tools like this, parents can shift from pushing their kids to secrecy to creating a trusting relationship through honest communication. This way, your child knows that they are safe, supported, and ready to navigate the digital world with you by their side.

I’m the mom psychologist who will help you GetKidsInternetSafe.

Onward to More Awesome Parenting,

Tracy S. Bennett, Ph.D.

Mom, Clinical Psychologist, CSUCI Adjunct Faculty

GetKidsInternetSafe.com

Works Cited

[1] https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/07/28/parenting-children-in-the-age-of-screens/ [2] https://www.ucf.edu/news/apps-keep-children-safe-online-may-counterproductive/ [3] https://arxiv.org/pdf/2303.09008 [4] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0140197117302051

Photos Cited

[1] Rizki Kurniawan [2] Marten Newhall [3] Tasha Kostyuk [4] Vitaly Garievhttps://unsplash.com/