I’m happy to report that Alanna’s conclusions were consistent with mine in my earlier GKIS article series on infant and toddler development. However, it gets complicated! In part one of the series, “How A Mom-Entrepreneur’s Dream Became the Multimillion Dollar Baby Einstein Company” we reviewed the development and booming success of the Baby Einstein Company based on hopes for launching digital education for infants and toddlers. In this article, you will learn how Baby Einstein’s monopoly faced competition in the early 2000’s and whether Mrs. Clark’s hopes were evidenced in the psychological research. In other words, is screen media use by children aged 0 to 2 beneficial or detrimental to development?

Current Rates of Screen Use by Infants & Toddlers:

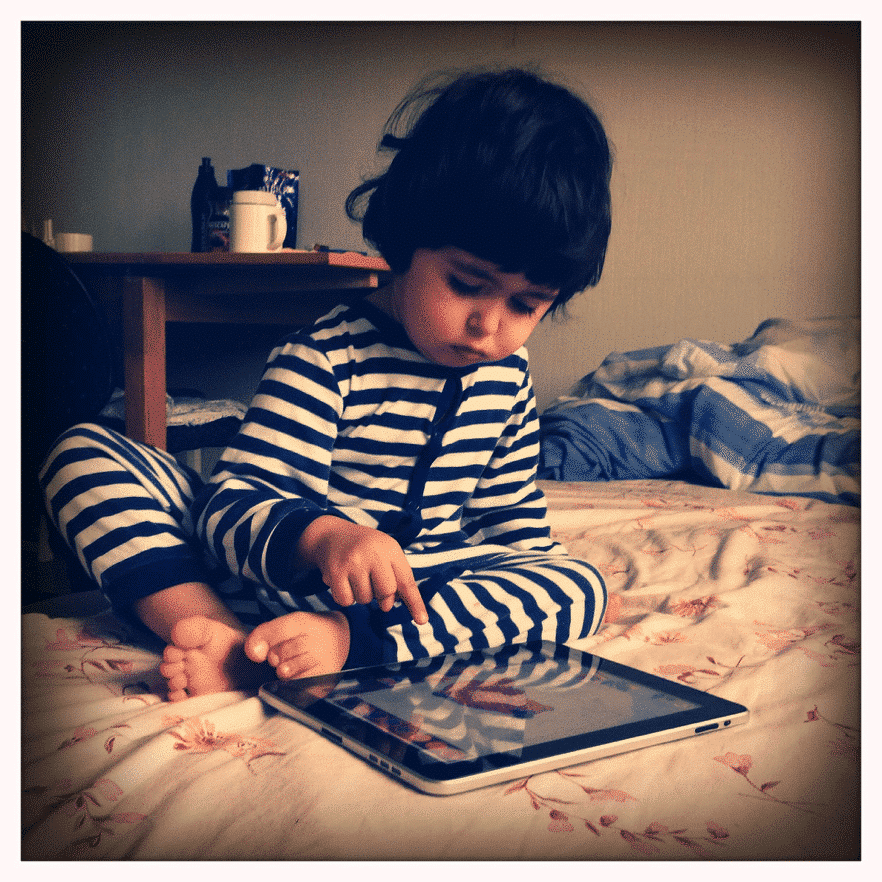

It is increasingly commonplace to see infants and toddlers interacting with screen media. A survey conducted by Common Sense Media found that between 2011 and 2013, the rate of children under the age of two who have used a cellular device rose from 10% to 38% (Rideout, 2013). More recent surveys demonstrate that one-third of children have scrolled, watched a television program, and/or played games on a smartphone before their second birthday (Kabali et al., 2015). This is partly because parents are becoming more reliant on screens to entertain and teach their older children – and now, infants and toddlers. A 2005 study found that one in five of children aged 0 to 2 even have a television in their bedrooms! Seventy percent of these same children were engaging in media use beyond the designated guidelines outlined by American Academy of Pediatrics of the time (Vandewater, Rideout, Wartella, Huang, Lee & Shim, 2007). Is this access to technology an awesome opportunity or is it harmful to young minds?

Passing the Torch

Just as Baby Einstein enjoyed enormous profit based on parental hope, so have more recent competing companies like Leapfrog. For example, Leapfrog’s mission is to “create award-winning educational solutions that delight, engage and inspire children to reach their potential…with solutions that are personalized to each child’s level.” Leapfrog sells DVDs, videos, and even tablets specially designed to facilitate pretend play and teach math skills, social skills, and creativity to infants and toddlers. According to the online resource Enterprises (2016), Leapfrog boasts huge annual profits to the tune of $67.2 million.

In addition, the company Brainy Baby, markets to parents of infants and toddlers with interactive DVDs that offer lessons about spelling, counting, reading, shapes, animals, and even foreign languages. However, unlike The Baby Einstein Company, the educational value of Brainy Baby’s products have been supported by university conducted, peer-reviewed research. Their website boasts about findings that have shown their products enable children to learn 22 times more than a child not exposed to the products. However, it is important to consider the company sells a variety of outlets for education, including books, flashcards and games, not just DVDs.

What the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Suggests:

When I began writing this article, I intended to provide a comprehensive view of the pros and cons of screen use in children aged 0 to 2 (the target age for Baby Einstein Company videos). However, upon diving into the university library resources, I was disappointed to find that little research has been done on the topic. In fact, without ample research, risk versus benefit of screen media use among little ones remains controversial.

Even the well-respected American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) have altered their views on screen use without evidence-based conclusions. Between the years of 2011 and 2014, the AAP released a statement saying “the AAP discourages media use by children younger than 2 years.” However, in order to avoid alienating parents of young children and to be more in-line with case study experience, they changed their statement in 2015 suggesting that “parents set media limits for their children based on the individual child” (Center on Media and Child Health, 2015). According to the AAP, this change was enforced because from their perspective “scientific research lags behind the pace of digital innovation” (Shapiro, 2015).

The Research:

Taking a look at Piaget’s classic theory on the stages of development, children age zero to two are undergoing the sensorimotor stage. In this stage, learning largely revolves around movements and sensations as well as receptive and expressive language (McLeod, 2015). According to Dr. Vic Strasburger, a spokesperson for the American Academy of Pediatrics, babies require face-to-face interactions in order to learn and are not able to achieve this type of stimulation solely from watching television or videos or even interactive screenplay. Not only does screen use risk replacing critical learning opportunities at the moment of use, it may also interfere with crucial wiring being laid down in their brains during the early stages of development. A deficit of face-to-face interaction due to too much screen time may result in long-term learning delay (Park, 2007).

Here is what the early research concluded about Baby Einstein and infant development:

- A 2007 study of children ages zero to two (who were viewing approximately 2.3 hours of television per day), concluded that infants with more exposure to Baby Einstein videos actually had weaker language development than their less exposed counterparts (Zimmerman, Christakis & Meltzoff, 2007).

Here are findings from more recent research:

- There was no clear negative association between media use and language development.

- Infants with no exposure to media actually had lower levels of language development than those with some exposure, suggesting that perhaps moderation is key.

- That expressive language was enhanced, but not receptive language. In fact, no influence at all existed in the older toddler age groups (Ferguson, 2014).

- In another study conducted in 2014, increased amounts of media exposure in infants have been linked to problems with self-regulation, meaning they have more difficulty monitoring their behaviors, thoughts, and emotions (Radesky, Silverstein, Zuckerman, & Christakis, 2014).

What Does It All Mean?

It is important to note that unlike the 2007 study, the 2014 follow-up study did not test infants exposed only to Baby Einstein videos, but a variety of different screen content. Sesame Street (which has been proven to have educational value) as well as Spongebob Squarepants (having little-to-no educational value) were even included in media viewing (Ferguson, 2014). Both studies were also correlational, meaning that they relied on survey results from parents rather than an experimental design, which demonstrate causal effects. This type of data can often be unreliable as parent memories of their child’s media exposure is not always accurate, leaving the applicability of the research limited. It can even be inferred from these studies that relying on videos alone, such as Baby Einstein, do not translate to intellectual growth. Rather, it is how we as parents use media to facilitate learning that determines if and how our children learn.

Using screen media in moderation, especially interactive activity like video conferencing and touch media, may elicit more interest in learning from toddlers. Also, repetition of concepts may be easier to achieve on screen with the supervision of a parent to help facilitate learning (Kirkorian, Wartella, & Anderson, 2008). Different modalities for education create new pathways for storing information. These pathways lead to better fact/concept retrieval later on. Since our children’s brains “remodel” throughout our lifespan with a “use it or lose it” system, screen media may enrich experiences, thus building new neuronal pathways that can be built upon for deeper and more varied learning potential.

What’s Next?

Although the modern education of children is beginning to rely heavily on the use of multimedia, there is a limited amount of research on the potential benefits or harm that can result from screen use in the toddler age group. As technology continues to become incorporated into our daily lives, media exposure of children is nearly inescapable. If the scientific research currently available provides little information about the subject matter, then it is up to us to share as much information as possible for the best education of our infants and children.

I’m the mom psychologist who will help you GetYourKidsInternetSafe.

Onward to More Awesome Parenting,

Tracy S. Bennett, Ph.D.

Mom, Clinical Psychologist, CSUCI Adjunct Faculty

GetKidsInternetSafe.com

Works Cited

Brown, A. (2011). Media Use by Children Younger Than 2 Years. Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/128/5/1040

Center On Media and Child Health. (2015). Media Use by Children Younger Than 2 Years. Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/128/5/1040

Enterprises, I. L. (2016). LeapFrog Reports Second Quarter Fiscal Year 2016 Financial Results And Other Actions. Retrieved from http://www.leapfrog.com/en-us/learning-path/videos/best-toys-for-2-yearolds

Ferguson, C. J., & Donnellan, M. B. (2014). Is the association between children’s baby video viewing and poor language development robust? A reanalysis of Zimmerman, Christakis, and Meltzoff (2007). Developmental Psychology, 50(1), 129-137. doi:10.1037/a0033628

Hilda Kabali, M.D., pediatric resident, Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, Pa.; Jenny Radesky, M.D., assistant professor, pediatrics, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Mass.; Susan Neuman, Ph.D., professor and chairwoman, Teaching and Learning Department, Steinhardt School of Culture, Education and Human Development, New York University, New York City; presentations, April 25 and 26, 2015, Pediatric Academic Societies, San Diego, Calif.

Kirkorian, Heather L., Ellen A. Wartella, and Daniel R. Anderson. “Media and young children’s learning.” The Future of Children 18.1 (2008): 39-61.

McLeod, S. A. (2015). Sensorimotor Stage. Retrieved from www.simplypsychology.org/sensorimotor.html

Park, A. (2007, March 06). Baby Einsteins: Not So Smart After All. Retrieved from http://content.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1650352,00.html

Radesky, J. S., Silverstein, M., Zuckerman, B., & Christakis, D. A. (2014). Infant Self-Regulation and Early Childhood Media Exposure. Pediatrics, 133(5), e1172–e1178. http://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-2367

Rideout, V. (2013). Zero to Eight: Children’s Media Use in America 2013 | Common Sense Media. Retrieved from https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/zero-to-eight-childrens-media-use-in-america-2013

Shapiro, Jordan (2015) Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/jordanshapiro/2015/09/30/the-american-academy-of-pediatrics-just-changed-their-guidelines-on-kids-and-screen-time/#670c06af137c

Vandewater E.A., Rideout, V.J., Wartella, E.A., Huang X.,Lee J.H., & Shim, M. (2007) Digital Childhood: Electronic Media and Technology Use Among Infants, Toddlers, and Preschoolers. Pediatrics, 119 (5) e1006-e1015; DOI: 10.1542/peds.2006-1804

Zimmerman, F. J., Christakis, D. A., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2007). Associations between Media Viewing and Language Development in Children Under Age 2 Years. The Journal of Pediatrics, 151(4), 364-368. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.071

Photo Credits

Business Baby Pointing by Paul Inkles, CC BY 2.0